THE MISSION

We learn and help our children learn

Vidyacharcha Kendra, with a mission to evolve as a ‘Community Pathshala’ has the motto — we learn and help our children learn. It gives the children an opportunity to learn in their own community environment. The mission is—

- to spread its concept and method of education to as many rural communities as possible;

- to regenerate community initiatives for educating their own children;

- to protect endangered community languages through their use in elementary education of children and thereby ensuring intergenerational continuation;

- to encourage transcreation of the study materials of Vidyacharcha Kendra in local community languages and to upload them as publications of the respective authors on this website;

- to request persons, groups or associations, who are socially active in the rural areas, and local communities to take up the concept and ideas of Vidyacharcha Kendra as their own initiative and improvise as per the local conditions; and

- to use this website as a platform for reporting such activities and interactions.

Free download the guidelines of the low cost replicable model, curricula, and study material of Vidyacharcha Kendra.

Rabindranath Tagore on community approach

More than a hundred years ago Rabindranath Tagore emphasised the need for a community approach in school education. On the Problems of Education [Shikshasomosya] he expressed that if schools could not become an inherent part of its surrounding habitation, they would become something imposed upon the community from outside. Such schools are dry and lifeless, and whatever we get from it is always through much effort but not useful in any application. Schools established in buildings with compartmentalized classrooms take the shape of boarding schools. They do not bear any pleasant impressions—they belong to the same category of barracks, asylums, hospitals, or jails.

Tagore also said that we may create perfect imitations of schools with benches, tables and teaching procedures, but those become only a burden on us. We must know our communities, and tune to their ideas and emotions. In another essay On Education Reforms [Shikshasangskar] Tagore mentioned that time had come that we took education in our own hands. The apparent autonomy, which we get under the permission of the government to cater to our specific education needs, is fallacious and most dangerous. There is no doubt that we must give our own efforts for education. If we fail to innovate and initiate our own system to educate our children, we would perish in all respects.

The method of education in Vidyacharcha Kendra

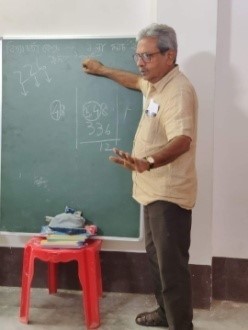

The method of education in Vidyacharcha Kendra is simple and yet quite different from the pedagogic model of modern school education. It is a low cost replicable model for the rural communities. There are no ‘masters’ giving teaching instructions here. Every afternoon a mother or elder sister-like person of the village (called ‘Didimoni’) sits for 2 hours with 15–20 children in her premises to assist them in their education from the pre-primary to primary level. Along with the children, the local educator (Didimoni) also studies the books of Vidyacharcha Kendra to educate herself appropriately and to know what the children should learn and how to help them proceed step by step in learning. Thus, it is a process of mutual learning — we learn and help our children learn.

The books of Vidyacharcha Kendra, unlike the school textbooks, which are primarily teacher oriented, keep this particular requirement in focus—to be useful to both the local educators and the children. Using these books, the local educators with some school level education may help the children learn. The objective here is clear— help the children learn through proper understanding and practice of the basics of education, not just make them cram the lessons of the school textbooks, as done in coaching centres.

No big ceremonies as in school education

In Vidyacharcha Kendra, unlike schools, there is no big ceremonies or grandeurs about education that tend to intimidate the rural children — there are no buildings of brick and stone with compartments of classrooms, no tables, chairs or benches, and no school bells, or registers, rules, or factory-like disciplines and code of conducts for the children. Children do not have to wear uniforms and shoes, and carry bagful of voluminous schoolbooks and workbooks each and every day. Vidyacharcha Kendra consciously avoids these, so that its main objective—helping the children learn—does not get obliterated in the institutional rituals and ceremonious grandeurs in the name of educating children that often lead to a mega-mania—attraction towards doing something big. For example, in West Bengal, a student in class I (age 6+) is supposed to study in an academic year (about 180 days) three big-sized massive textbooks (663 pages)—Amar Boi (524 pages), Health and Physical Education (60 pages), and Sahajpath (79 pages). How could this be possible? Naturally, here class-hour based teaching would mean at the most giving some instructions to the students to study some specified pages of the books, and the students could only open the books to give merely a cursory look at those pages. That is all about education at schools nowadays. So the students have to learn with the help of either their parents or private tutors at home.

Specific lesson plans and manageable textbooks but no language barriers as in schools

In the rural schools the qualified and trained (D. El. Ed.) teachers appointed as per statutory rules are often outsiders to the local community and speak a language or a dialect different from the vernacular. Children can hardly understand or follow the instructions from such teachers. Such language barriers between the teacher and the student never arise in Vidyacharcha Kendra. The local educators explain the lessons to the children in community language. In fact, when children are suddenly exposed to a number of languages simultaneously, before learning their native language properly, they become bewildered. Their thinking process and ability to logically understand and comprehend become incoherent. By learning through their own language the children understand the lessons much better and thus get an appropriate foundation of learning from the very beginning of basic education.

Practising the community approach over the years, Vidyacharcha Kendra has been able to bring out a clear guideline of its method of education. A detailed lesson plan is prepared listing by stages what and to what extent a child should learn at pre-primary and primary levels. Secondly, following the lesson plans, study materials appropriate for the children and their local educators in the form of small books on Bengali, English and Mathematics are prepared. To keep the size and shape of these books manageable and easy for the children to handle, unlike those intimidating huge schoolbooks, all the unnecessary repetitions, confusingly loud colourful pictures, and the big font size of text letters (though hypermetropia is not common among children) are carefully avoided.

The problem of year-wise batch processing in schools

The pedagogical model of formal schools not only imposes a teacher-student divide, it also divides the students into batches of class by academic years. Presuming that students progress more or less uniformly in learning, all the students in a class are taught the same lessons with the same teaching instructions in class-hours using chalk and board (sometimes online nowadays) to complete the syllabus for the academic year. After the academic processing in a year, the learning progress of a student is measured by a qualifying examination for promotion to the next class for further processing. This appears to follow principally the same method of batch processing by stages in factory production.

In school education there are 12 such stages or classes (1 to 12, specified by age 6–17) of the children. In factory production we see rejections of products at every stage of processing that fails to qualify as per the standard specified. In school education we see similar rejections but call them dropouts.

The problem with the pedagogical model of school education is that children never progress uniformly in learning. Yet, in the tight academic schedules of class-hours there is no scope for the teacher to give individual care — allowing those who finish a lesson to start the next lesson while helping those who are yet to finish to practise more.

Individual care — no year-wise batch processing

The method of education in Vidyacharcha Kendra sharply differs from the pedagogical model of school education. Children are not divided in year-wise batches of class and the lessons are given not in schedules of class-hours. By the stages of lessons there are basically two sets of children. Tentatively their age groups are 3+ to 6+ years, and 7+ to 10+ years. They sit and study together using their respective study books. The foundation of learning that the children get in Vidyacharcha Kendra as beginners in the first age group enables them to study the textbooks of Vidyacharcha Kendra on their own, when they come to the next stage. They require minimum help from the local educators implying they have learnt how to learn.

There are no common lessons or common instructions for all. Those who finish a lesson are shown how to study the next lesson and those who are not able to finish yet are helped to overcome their difficulty and practise further. Thus, those who can advance may advance, while those who are stuck up at the moment get the time to practise more and pick up. This individual care is almost impossible in batch processing method of formal education by class and academic years.

Education flows in a continuous process in Vidyacharcha Kendra — as and when the children finish the first group of lessons (for the age group 3+ to 6+) they take up the lessons in the next group (7+ to 10+ age group) and complete study up to class 5 of formal schools. While some children leave after completion of study up to this level, some new children join the first group and the ‘Community Pathshala’ continues to cater to the educational needs of the children of the village.

An unfulfilled dream in Indian education

As Vidyacharcha Kendra spreads over different areas with different local conditions its evolution continues in the local contexts, changing the framework and breaking the barriers of notions and ideas that tend to become rigidly set in our approach. This flexibility helps Vidyacharcha Kendra continue to evolve and adapt to local conditions.

A major hurdle still remains to be overcome is the language of the study materials or the so-called medium of instruction. Is it not an absurd situation that a Santhali, or a Rajbangshi, or a Kurukh or Oraon child, even at the beginning of elementary school education, would need to learn Bengali first to read and write in Bengali, and then through it learn English and Mathematics? For a true community approach to education, we need elementary textbooks for pre-primary and primary levels in the local community languages, whether such languages have their own scripts or not. If not, it may be possible to use any other script for the language — Bengali, English, or Hindi, as may be suitable for the community.

Early schooling in a child’s mother tongue, recommended in the new National Education Policy (2020), is not really new. Article 350A of the Constitution of India (1949), Kothari Commission (1964–66), and then the Right to Education Act (2009) also mentioned the importance of mother tongue as medium of instruction in early schooling. Yet, it remains as an unfulfilled dream in Indian education. Perhaps the task is beyond the scope of the State initiative. We need community initiatives to achieve this goal. Vidyacharcha Kendra therefore has its mission — reforming education through community initiatives.

Regenerate community initiatives, not suffocate it

Over the last few centuries communities in the rural areas have been losing their initiatives and thereby identities all over the world. Like bio-diversities, the cultural and language diversities are also getting lost. Till the early twentieth century there was colonial encroachment and dominance. Then came the sovereign national State initiatives followed by private business initiatives squeezing the space of community initiatives.

Unfortunately, a more recent phenomenon of social work initiatives, in spite of all good intentions to do something for the villages, sometimes snatch away the community initiatives by overdoing. It is not uncommon in the parlance of CSR (corporate social responsibility) and among the celebrities to talk about “adopting” some villages, as if they are orphans! Some groups of social workers and activists, perhaps with similar notions at the back of their mind, tend to follow suit. They frequently visit villages and ceremoniously donate products of urban lifestyles, try to educate the villagers in urban ways of life. Actually, these visits often serve the purpose of tourism for them. This disturbs and suffocates the community life of the villages and affects their self-reliant growth from within. Vidyacharcha Kendra carefully avoids this approach of social work. Education for rural children needs a peaceful and quiet environment where it becomes an activity inbuilt in the local culture and everyday life and undertaken through the community’s own initiative. It cannot be imparted through massive ceremonies organised by outsiders in the name of education. Vidyacharcha Kendra may act only as an initiator to regenerate the community initiative for educating their children, with no intention to replicate and impose the models of urban schools or way of life.